Post-Mortem: The End Times' 2008

This has been, to return to the cliché, another odd year. To wit: the first job I’ve ever kept for more than 3 months (and, for the purpose of the company finks who monitor this thing, a lovely job it is too), my first festivals (Instal in resplendent Glasgow, Supersonic in a sweating Birmingham July), and the move to university (itself fraught with issues I never thought would arise from my stony black heart). The latter has had some interesting results which it would incorrect of me to draw conclusions from now. (If you wish to know why I don’t mention the more obvious things that happened this year – oh, worldwide economic downturn, an African-American becoming President-Elect of the United States, the final disintegration of George Bush’s presidency (and his reception of a fragment of his proper comeuppance) – then note the fact that I only began watching television news and reading newspapers since I came back from university. I simply didn’t care.) These facts also begin to explain the fact that this blog has gone on the backburner in recent months (and don’t think I haven’t noticed my demotion/disappearance from some blogrolls.) In other ways, it has been Business As Usual. I spent 10 months of 2008 as a 19-year-old – considered, biologically speaking, the supposed best year of life (and, after all, no-one seems to care for much except bare biology these days). Occasionally I scold myself for having seemingly wasted it, although I seem to have done both more and less than was allegedly expected of me. In simple terms, a significant amount of good stuff happened, but, due to what appears in retrospect as a dawdling unconcern – indeed, an acedia – a significant amount was avoided, exacerbating the usual sense of lack. On balance, 2008 was at least better than a kick in the teeth.

Anyway, I listened to some records as well this year. There’s a list of the ones I thought best below; 2008 seemed more abundant than last year (or previous years, for that matter) perhaps simply because of the fact that, for the first time, I had purchasing power of a sort. Differing opinions regarding the fecundity of this year are to be expected nowadays. There was certainly far too much good music for me to keep up with, but then again super-abundance of everything (including, undoubtedly, utter bloody dross) is the characteristic of our period (perhaps the economic crisis will have some effect on this, but I doubt it.) I shall, like Kek-W, make no predictions; I prefer, now, to be surprised, in any case.

As always, I’ve found other people’s choices quite baffling, but that seems to be the way of things. I can offer no justifications for my choices other than that liberal catchphrase ‘personal opinion’; or, perhaps better, ‘love’.

So:

Sounds

The 15 Records I Loved The Most in 2008

1. Xiu Xiu – Women As Lovers

I remain bewildered that this has been barely mentioned in the Year End lists I’ve read so far. Not merely the best release to date of one of the most consistently envelope-pushing bands on the planet, but the album that has affected me most this year: loving, harrowing, regretful, splenetic, politically engaged, hilarious, hopeful. To go into the deeper reasons would involve too much verbiage and self-revelation; it has partially to do with the fact that this is both the queerest (in Lee Edelman’s sense) and the most human (in a good way) release I’ve heard. Jamie Stewart and Caralee McElroy, aided by storming performances from Oakland compatriots Ches Smith, Devin Hoff and Greg Saunier, have refined their own brand of electronically-damaged, digitally-spliced, finely-focused song to a keen knife edge (and made arguably the best track of this helio-cycle in their Michael Gira-assisted version of ‘Under Pressure'. Just to say.)

2. Birchville Cat Motel – Gunpowder Temple of Heaven

The final release from Campbell Kneale under the BCM moniker, and perhaps his best; the most convincing appropriation and extension of modernist drone music (La Monte Young, Charlemagne Palestine, Olivier Messiaen) by punk/noise praxis (alongside Kevin Drumm’s leviathan Imperial Distortion). More than that: a holy moment extended to 40 minutes, an unrivalled example of how to create the most mesmerically shifting music within stasis; a dream of light – a companion piece, in a certain sense, to Richard Youngs’ astonishing Advent (see below). Add to this the beautifully-designed Gothic packaging and eloquent Bruce Russell-penned liner-notes, and you have a gravestone for the project to last the ages.

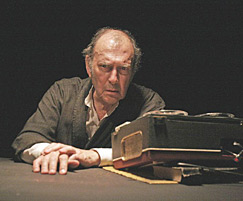

3. Philip Jeck – Sand

Not admittedly, his best work, but, still, hypnotic and achingly evocative, reminiscent of nothing so much as Stan Brakhage’s slurred-shape light-scapes, with the added poignancy of the archive’s dust. The latter part especially pertinent to a year in which the mainstream, still beholden not merely to the music of 40 years ago, but to its imitators of the last ten, twenty years, struggled to produce anything worthwhile. Who would have guessed ELP would ever be involved in something this good?

4. The Bug – London Zoo

Despite its considerable eloquence, I remain unconvinced by Carl Impostume’s critique of London Zoo. Or I would if I had bothered reading the entirety of it; I spent the time listening to, and enjoying it, instead. Admittedly, the mid-album run of ‘Fuckaz’, ‘You And Me’ and ‘Freak Freak’ I find slightly dull when in an impatient mood; but otherwise it perfectly sculpted urban paranoia in sheer bass weight. (No doubt those actually living in London will find it has even more resonance: its millenarian atmosphere seems ever more suited to a city whose economic structure almost collapsed in one day, and whose populace is protected from global warming by nothing but a concrete spine; if Owen or Infinite Thought feel like writing that review, I’d be more than happy to read it.) Aside, of course, from the fugged-up fear, there was also the sheer visceral force, aided by consuming wholesale the dubstep that Martin himself presaged, and the UK dancehall it first took inspiration from: ‘Poison Dart’, the double-shell assault of ‘Warning’, the re-honed righteous fury of ‘Jah War’, ‘Murder We’s atomic bounce.

5. Skullflower – Desire For A Holy War

It never ends. It’s becoming apparent there will never be a definitive Skullflower release – this certainly isn’t it; Matthew Bower’s twenty-plus year-old noise project will simply keep on producing endless variations of itself, like a species with an accelerated evolutionary process. Taking its cue from the dark-star feedback of 2007’s Tribulation, this is founded so much on sheer bloody noise it becomes almost spectral – endlessly layered films of guitar shredded so painfully it becomes impossible to distinguish as such (except when one central riff, as on ‘Moses Conjured A Blood Niagara’, breaks through), one blasting current bleeding into the next. This remains somewhat far, though, from the crushing pseudo-Goth darkness of his IIIrd Gatekeeper period; its sheer harshness somehow alchemises it into a disorientating white-light vision.

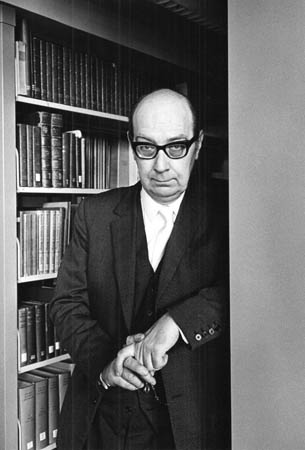

6. Alter Ego/Gavin Bryars/Philip Jeck – The Sinking of the Titanic

Before you start, I know very well that this was released at the end of 2007. However, I give not a toss for chronology when it comes to this. I’m simply not qualified to write anything more than the simply factual about this – if you want that kind of thing, I suggest you read The Blue In The Air’s Year-End list, whenever it plans to appear. So, simply: it’s incredibly beautiful, heartrendingly poignant, intelligent (that a mere thought experiment would yield this!), bottomlessly resonant, quivering through the fabric of history and memory. It is also, unlike some of the records on this list, a relatively easy ride (it is, for example, possible to simply listen to it whilst reading), without being in the least flaccid (unlike, say, that Aidan Baker release I reviewed for Plan B…); the playing by both Alter Ego and Jeck is measured, tender, co-operative, and simply lovely.

7. Runhild Gammelsaeter - Amplicon

The avant-metal equivalent of a sympathetic biology lesson, its sutures between racked screams, acoustic strums, and battering electricity straddling the organic/inorganic divide. This year, reading nature books, meeting poets intensely interested in biology, it's been all about the science; the fact that Gammelsaeter has a PhD in cell physiology only adds to the interest of this chaotic meditation on life's origins and course. An amplicon is the result of the artificial replication of a single DNA piece, the expansion and proliferation of the organic (it's worth noting Cage's thought that sound is essentially a marker of being, of life). Deeply strange, compelling, harrowing, life-affirming.

8. Peter Brotzmann/Mats Gustafsson/Paal Nilssen-Love – The Fat Is Gone

I may be reneging on whatever futurist principles I have by including this: not only is it technically 2 years old (recorded at the 2006 Molde Jazz Festival in Norway), but these guys aren’t exactly making any formal advances on the transatlantic action-jazz movement which Brotzmann, in effect, founded with his run of late 60s recordings (For Adolphe Sax, Machine Gun, Nipples, etc.), and which has been riding high in the past decade or so. Still, I couldn’t really give a fuck. ‘Bullets Through Rain’ hits like a crowd-control firehose; the creeping alien soundscapes of the other two tracks, ‘Colours In Action’ and the title cut, the latter gradually erupting into a shrieking rave-up of monumental proportions, seduce and destroy. Reason enough.

9. True Swamp Neglect – Cloud Cloud Cloud

On CD Baby, this is included in the geographical category “UK – England – South-West”. It still gratifies me to see it spelled out, even though they deserve far better than to be ghettoised as a ‘local band’. Though the hype that accompanied their first release dissipated during Cloud Cloud Cloud’s lengthy gestation, it still baffles me that this superior album has met with critical silence, except from the expected quarters. Its wholly pleasant Pavement-The Fall-Beefheart first half (highlight: ‘Map of the Map’), is balanced by the second half, which sets the controls for the heart of the sun. ‘Providence’ (the Sonic Youth one) remake ‘Young Vampire’ sets the scene for the face-shredding blow-out of ‘Dry-Eyed Riot’, leading perfectly to the ‘Plague of Lighthouse Keepers’ sequel of a title-track. Drifting, exploratory, unexpectedly poignant (section 4, ‘Chess Party’, has had me nearly in tears more than once), it’s one of the things I’ll carry with me most from this year.

10. Abe Vigoda – Skeleton

Certainly, aside from the Vivian Girls' debut (which clocked in, on my copy at least, at 21m 58s, barely more than a somewhat slim EP), the shortest long-player I heard this year, and easily the most frantic and audibly vital(ist). The media's genre shorthand of 'tropical punk' cloaks music of audible desperation and genuine energising strangeness: literal energy music, each song beginning fast and ending so; Poundian fragments of text, delivered in collective off-key hollers drenched in warping reverb, guitars painted on with light, as if the master tape had been left too long in the sunshine, driven on by manic and often surprisingly funky drums. And before condemnations come in about obliquity, the lyrics - written by guitarist Juan Velasquez, who is Hispanic and gay in a city which marginalises both (LA) - are often strangely beautiful: "Hope is a white hand that moves through my body."

11. Boredoms – Super Roots 9

12. High Places – High Places

13. Portishead – Third

14. Lawrence English – Kiri No Oto

15. Angel – Hedonism

Honourable Mentions

Bill Dixon – 17 Musicians In Search of a Sound

The Week That Was – The Week That Was

Aidan Baker and Tim Hecker – Fantasma Parastasie

Peter Rehberg – Works For GV 2004-2008

Fennesz – Black Sea

Nalle – The Siren’s Wave

No Context – Lines To Follow Colour Changes In Leaves

Burial Hex – Initiations

Xela – In Bocca Al Lupo

The Ashcan of History: Top 15 Old Records and Reissues Heard in 2008

1. Richard Youngs – Advent

This is going to be one of those anecdotes which never goes away. It remains a mystery whether this really happened or not, but I have a memory of seeing, from a train window going towards Berwick-Upon-Tweed, en route to Glasgow for the Instal Festival, the sea shimmering far out below the sheer cliff face next to us, the third section (or was it the second? Were those lyrics I remember?) from Advent, in which his piano, endlessly cycling through the same chords, struggles, drugged, through an endless cascade, a curling, lambent firmament, of piercingly bright guitar overtones, blasting away. Having said all that, it remains difficult for me to say what the significance of this was. Perhaps “the one moment where beauty and truth aligned” will do the job. Not merely the most beautiful album I’ve heard all year, but one of the most haunting, nerve-shaking, astonishingly resonant albums ever made.

2. Kate Bush – Hounds of Love

Not quite ditto. Almost, though, even if just for ‘Running Up That Hill’. Which of course it isn’t just about. The only track on the first side I don’t get the biggest swell of joy imaginable from is ‘Mother Stands For Comfort’, but then it just sets off the sheer wonder of the others. The second side, a magnificently Woolfian concept suite called ‘The Ninth Wave’, is something I’ve yet to fully get to grips with, but the terrifying sense of claustrophobia on ‘Under Ice’, the Burroughs-via-Arthur Russell avant-disco collage of ‘Waking The Witch’ (that voice: “BLACKBIIIIIRD”), ‘Jig of Life’s rampant abandon and guiltless appropriation of Other musics, stand out absolutely as diamond-hard points of (icy?) profundity. The fact that the most mind-(and-heart-)boggling track here, the aforementioned ‘Running…’, shares, to a great extent, the language of ‘80s pop’ (those synths, that drum-machine, that same bloody gospel choir and OTT guitar), makes it all the more amazing; this is pop music (in the sense of ‘popular’, as in motherfucking No. 1 on the charts) as alchemy, as shamanism, mediumship. The fact that she stays absolutely true to a decidedly idiosyncratic aesthetic is only more excellent.

3. Robert Wyatt – Rock Bottom

No, since you ask, not the reissue edition – though it was lovely to see Wyatt get his due vis-à-vis having his entire oeuvre back in print, in a lovingly-presented state, I actually bought this one sometime in January from Sounds in Boscombe, having gone in on the off-chance. Torch songs delivered in a whisper, nonsense poetry as millenarian glossolalia, songs built on weird see-sawing synth drones which stick in my mind as fast as the ‘hookiest’ pop, a most strangely English of pop albums whose most skin-tinglingly lovely song is basically free jazz played by a South African and some bods from Kent (and tailed by a recital from a Scottish poet) – paradox on paradox. What’s explicable enough is the strange, sighing, glittering poignancy of this record; humane, funny, seductive, breathlessly lovely (especially on the swaying coda of ‘Sea Song’ and ‘Little Red Riding Hood Hit The Road’, with the mighty Mongezi Feza on trumpet), self-deprecating, harrowing, ultimately hopeful.

= 4. John Coltrane – The Major Works of John Coltrane

= 4. Albert Ayler – disks 1-5 of Holy Ghost

One has to attempt Everest at some point. The Major Works is a compilation document of the extraordinary period in mid-to-late 1965 in which Coltrane organised and recorded Ascension, OM and Kulu Se Mama, just prior to the addition of the young firebrand percussionist Rashied Ali, which would precipitate the disintegration of the ‘classic quartet’. It took me almost a year to listen to ‘Ascension’ (both editions) properly; the sheer density, the whirling vortex of musical movements, leaves me with a huge number of depths still to be explored in this. The other tracks are slightly less daunting; ‘OM’, in particular, is quite brilliant, with Trane and Pharoah Sanders practically cracking their reeds and bursting lungs over a polyrhythmic storm from Elvin Jones and two bassists; even the bookending chant (“the clarified butter”, indeed!) is pretty convincing in this setting. Holy Ghost, the reissued Revenant boxset of live recordings from various incarnations of Ayler’s band (along with demo tapes recorded with just Mary Maria/Parks) is similarly (sorry) transcendental. The knotty madness of recordings with Cecil Taylor and Burton Greene, and his recordings with bassist Gary Peacock, pioneering free drummer Sunny Murray and Don Cherry, contrasts strangely with the bizarre air of the quintet recordings with his brother Ayler’s brother, Donald, and French violinist Michel Samson. A folksong-y (in a Charles Ives sense) penchant for melody is put through a mangle of fractured dissonance, the musicians breaking off in all directions, with total disregard for the ‘proper’ uses of melody (like Charles Ives!) Aside from the searing energy of the improvisations, the sheer love of sound-as-sound, the shattering seagull cries of the brothers seeming to access something else. Just because David Keenan says so, doesn’t mean it’s bullshit. Stirring, profound, incredibly important.

5. Roxy Music – Roxy Music

It’s difficult for me to articulate exactly why Roxy Music are important, partially because my own reaction is made up of so many different things: the backstory; the theory; the knowledge that so many others have all said what I might say before, and in a better way; the sheer bloody thrill of it all, of this album. I could refer you to a million sources, but won’t. Roxy are not just included in this list because they were a locus of energy in their own time, and an important example to our own, but because the album is so exciting to listen to. I’ve said this shit enough times before, so I shan’t go any further.

6. GAS – Nah Und Fern

The grey swathes of winter had a soundtrack too good for them. The grandiosity, Gothic-Goethean romanticism, and globular, psychedelic enswathement of these four disks – particularly the dark arborean meditations of Zauberberg and Konigsforst – were too fascinating to be listened to just as background music, so had to wait until I had my room back in Bournemouth. These last few weeks have, thus, been absolutely lovely, drawing lines between my house, the swiftly dwindling woods around Littledown where I read as a teenager, the mud avenues of the New Forest…

7. Cobalt – Eater of Birds

When, having read Joseph Stannard’s manic recommendations, I found this album at Burial Hex’s Bristol show in April, it was, evidently, fate (maybe). Whilst, having bought perhaps two metal albums in the past 3 years, I’m in no position to judge, this is probably the most relentlessly scourging, emotionally excoriating album I’ve heard since The Holy Bible. If the preceding 50 minutes of feedback-ragged, laser-sharp riffing and firestorm drums weren’t enough, the ravaged, life-threatening screams and napalm guitars of the closing title track would easily finish the listener off. Astonishing.

8. Tricky – Maxinquaye

Another whose depths remain, I think, mostly unplumbed, but still the sweaty, erotic, paranoid fug of this proved irresistibly addictive. Bought on a sweltering July day at Birmingham's MVE (a good omen, if there ever was one), the earworms of Martina Topley-Bird's strange cross-gender ventriloquism (especially on 'Aftermath' and 'Ponderosa'), its astonishing puncta of beats ('Overcome' - how's that for a fucking rhythmic background!), its renegade intellectual prowess and feel for atmosphere (the Blade Runner sample on 'Aftermath', the transmogrification of 'Black Steel', the shotgun-click percussion on 'Strugglin'') seriously possessed the hermetic chamber of my room at university. This, unfortunately, is a situation that may have to change.

9. Cecil Taylor – Conquistador!

One of the pieces I attempted to write for this blog this year was a piece on the free jazz I had been listening to. I stumbled at near-enough the first hurdle: writing about this extraordinary agglomeration of musical forces, a rare document of one of the most important development periods in free music. Recorded in 1966 by a sextet including two bassists (Alan Silva and Henry Grimes), the parched scattergun trumpet of Bill Dixon, Jimmy Lyons' obliquely inventive alto and Andrew Cyrille, a brilliant successor to Sunny Murray on the drums, it's hi-NRG and dense as fuck from start to finish, its thorny tangles of sound only yielding with intense listening. The second side-long track, 'With (Exit)', is slightly less unrelenting, but its long-strung lines of sonic ideas have their own distinct charms.

10. V/A – An England Story: 25 Years of the MC in the UK

The original Heatwave-mixed Blogariddims post was easily my most-listened-to podcast of 2007 and 2008 (a dubious honour, but work with me here), so I was ecstatic to see (and hear) this. A wholly necessary (secret) history lesson and a delectable selection of tracks - Suncycle's 'Somebody', Papa Levi's apocalyptic 'My God My King', Riko's jaw-dropping 'Ice Rink Vocal', later junglist toaster General Levy's slamming 'Champagne Body', manic missing link London Posse, desperate Brit-hop from Blak Twang, the ladies out in force (Warrior Queen, Stush, Estelle and Joni Rewind's garage 'Uptown Top Ranking'). Superlative.

11. The Microphones – The Glow Pt. 2

12. AMM – The Nameless Uncarved Block

13. Pita – Get Out

14. Steinski – What Does It All Mean? 1983-2006 Retrospective

15. Mordant Music – Dead Air

The Top 10 Records I Should Have Bought in 2008, But Did Not

Asva – What You Don’t Know Is Frontier

By Any Means – Live At Crescendo

John Butcher – Resonant Spaces

Skullflower – Circulus Vitiosus Deus and Taste The Blood Of The Deceiver

The Caretaker – Persistent Repetition of Phrases

Sunroof! – Sufi Hate Crime/Zen Atrocity

Matmos – Supreme Balloon

Josephine Foster – This Coming Gladness

Zeitkratzer – Electronics

Scorces – I Turn Into You

Hat tip to Valter.

People Who I Saw Play Music In 2008

My list, helpfully, is over here, at the Plan B magazine forum.

Tops

In spite of everything written above, without doubt the best musical objects I received all year were: a copy of Animal Magic Tricks’ Soil EP, lovingly made by the sorceress herself; a stack of CD-Rs from my friend C. (including Advent – oops – and plenty else to keep me interested into the new year); and a birthday mix CD from another friend, T., which nearly had me in tears with the amount of love that had gone into it. Thank you all, if reading.

Books

Undoubtedly the book I read that meant the most to me this year Philip Hoare’s England’s Lost Eden: Adventures in a Victorian Utopia. It joined together channels of thought, stratum of my own history, in such an extraordinary manner, and in such measured, evocative prose, that I would have to call it the best and most important book I’ve read since Greil Marcus’ Lipstick Traces. His Spike Island was also powerful and haunting, and I look forward to reading his new one, Leviathan, published this September. The best actually recent book I read this year was A.L. Kennedy’s Day (published in paperback in 2008, so that’s my alibi). Enormously powerful, full of stony wisdom and written in prose so perfectly balanced it’s almost makes one want to pulp the laptop. My favourite book actually published this year was George Szirtes’ New and Collected Poems, a much-needed reissue of 4 decades’ output by one of Britain’s best poets. Neil Astley’s anthology Staying Alive, whilst not published this year, was certainly a constant comfort in poetry. Other highlights: finally reading David Toop’s Haunted Weather; Robert Macfarlane’s luminous The Wild Places; W.G. Sebald’s Austerlitz; Paul Morley’s heart-of-darkness memoir Nothing; two behemoths: Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook and Melville’s Moby Dick; most of Lester Bangs’ Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung.

Other

Party/gig at F.’s old house on Walpole Road in freezing January. Meeting Louis, Petra, Joe and Matt at Supersonic. Finally visiting Peterson’s Tower at Sway on a late summer afternoon. Seeing The Dark Knight, George Szirtes and Elizabeth Bletsoe on and around Warwick campus. Derek Southall’s Blackwater – 5 Years After and Stanley Spencer’s Portrait of Miss Ashwanden (the final work) at the Herbert Art Gallery, Coventry, and a copy of Rossetti’s Beata Beatrix at the Birmingham Municipal Art Gallery. Watching the University Chorus perform Taverner’s God Is With Us at Coventry Cathedral. Rocking out with C. numerous times in numerous places (especially at Gay Against You). Buying a hoard of much-loved books from Holdenhurst Books just before it closed. Kelvingrove Park and Volcanic Tongue on a beautiful February Saturday. Seeing everyone who I feel I should never have left.

Good luck to all with 2009.