Livings

The winter has closed in, thoroughly, on Bournemouth. The entire place is gripped by the kind of chill you would find in John Carpenter's The Thing remake (which, apparently, has been appropriately just been re-released on DVD.) Even mid-morning sunlight (at least, naturally enough, on my day off) is at best grey. Christmas cheer, as per usual, is everywhere offered, but little of it actually apparent; the weather, as usual, isn't right for it.

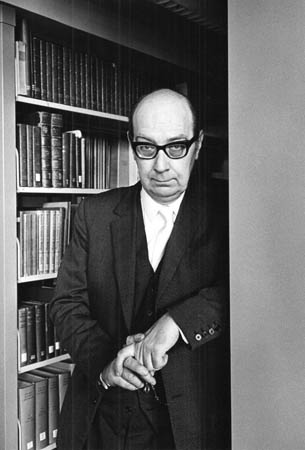

It was perhaps appropriate that I found myself, the other night, watching a very ashen face and listening to a very cold voice. I was watching, with my parents, Stephen Fry's Guilty Pleasures; strange inclusions aside (no-one should feel in the least guilty about liking Abba), the programme had some merit for Fry discussing poetry - his own work, apparently, remains unpublished, in spite of his being able to publish his shopping lists, if he so wished. He talked briefly about form, including a short remark about how, "With masters of the form, like Philip Larkin, you can this kind of pleasure just from their technical prowess". Cue black-and-white footage of Larkin's cue-ball bust prowling the halls of Hull University Library, his voiceover - like a particularly disappointed bachelor accountant, his throat thick with Victorian dust - reading out (I think) 'Talking in Bed'.

This is only even mildly interesting if you know that he was one of my favourite writers back in the day. When I was going through my Holy Bible phase, I learned that Larkin was one of Richey Edwards' favourite poets, quoting 'Money' on the inside sleeve of Generation Terrorists. We were going to be studying High Windows as part of the English course in Year 12; naturally, I went the whole hog and bought the Collected Poems. Reading through some of them again - 'The Whitsun Weddings', 'Dombey and Son', 'If, My Darling', and, of course, 'Aubade' - they're certainly good, as poems, but I doubt if there's very much 'enjoyment' to be found in them. Yes, technically they're excellent, sentiment and structure more often than not perfectly sutured together, his feel for words' music ("the skirl of that bulletin unpicks the world like a knot") is often impeccable. But it's strange, for someone who was so good, in pieces like 'An Arundel Tomb', at capturing life's texture, that they should feel so dessicated. Particularly in the late poetry, the overriding message that everything (especially life) is shit (especially nowadays, as opposed to some imagined pre-1914 world of immortal sunshine, cricket, and bloody imperialism) leaks even into the feel of language; in some polemic pieces like 'Going, Going', 'This Be The Verse' and 'High Windows', it essentially reduces the poetry itself to doggerel in service of the Countryside Alliance, but even in the better poems like 'The Building', the words seem so freighted with resignation, with the weight of hopelessness, that it's painful even to read. On the last day of Year 13 before my A-Levels, when I was seeing my friends for what has turned out to be almost exactly the last time, my friend R. mentioned Larkin - it was one my supposed identity signifiers that I was a fan. When I rebuked him, they were surprised. I replied, simply, that as good a poet as Larkin was, I didn't want to be him - right-wing, rootless, trapped by a loneliness so desperate death would seem preferable. Still don't, in spite of my multiple failures to avoid going down that path (there's still time, mind.) Is it alright to elevate ethical concerns (and, let's face it, questions of self-preservation) above issues of technical excellence? I think it is.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home