Tuesday, July 31, 2007

'Oh, Play That Thing'

--J.G. Ballard.

Machines have always been viewed as mysterious objects – not merely the evolved brother of the basic tool, but mystic enablers, the implacable mystery of the mineral world combining with the secretive guarding of the internal processes, a fascination deepened by the advent of computers: silicon, with a molecular structure closer to diamond than any metal, the halfway house between base metals and gold, becomes the inscrutable transformer of the physical. How we get from input to output becomes even more odd with instruments, these magickal talismans invoking the ghost of electricity to set humanity in fear and trembling one more time. Planet Monkey (a.k.a. Random Loop Generator), crouched over a collection of synths, at least one with its raw guts exposed, face hidden by hood, mask and goggles, seems to know just what to do with just such a feeling: abuse it. He seems to be a man who knows his sci-fi – the literature in which technology is distinguished by its ability to cause cold, pants-soiling terror. Or at least that’s what he wants to do: he spends the next half hour or so sculpting shapes out of static, sluggish beats and alarm-siren synth blurts. It undergoes the usual noise process of slow, organic shifting, introducing removing and modifying elements as he goes along. There were certain points where he got the construction just right, tweaking up the scraping-metal feedback to teeth-grinding levels. Unfortunately, this is where we hit my problem area with noise: if the idea is to terrorise the audience, then the fact that they have paid to watch makes it ultimately self-defeating. No matter how much evil sonic pain you throw at them, they’ll carry on sipping their pints (exactly what the audience in the Portman did.) If noise instead has the purpose of whipping the audience into a frenzy (this being Wolf Eyes’ approach), or of being confrontational on a psychic level (as with Whitehouse, or Maryanne Amacher) then a different approach is called for; the fact that Wolf Eyes are now sliding back into rockist good-time-music perhaps proves their isn’t much left to reap in the middle ground Planet Monkey harvests.

On a lighter note, Skitanja were excellent as always; having written about them before, you should know the drill by now. I would say that this time they played with even more absurdist frenzy, Steve Potatoes wrenching more brilliantly primitive noise from his guitar and the drummer mutating into a blur of limbs and exotic instruments at the drop of a hat. They even added an extended coda (I think) to ’77 And Mama Kiki’, for our pleasure, and the choice of Sin City as their backing film was appropriate in its brutality.

Far from routine was Animal Magic Tricks. As she took her place among keyboard, Fisher Price toy and guitar, I was wondering where the rest of the band was. And then… Jesus. The scene from Baron Munchausen in which Uma Thurman is revealed from inside a clam played as her transfixing voice emerged over toy melodies. Face close to the mike, eyes open then closed, breath transubstantiating… She started the next song, over minimal electronic waves: "Have you ever dreamed of pure love/And then found their heart was full of blood?" The sea shimmers, water on water the only sound; a body, like driftwood, washes onto the sand. Her stage presence, condensed down to the smallest core, was utterly bewitching; asking for a bit more volume on her IPod, introducing "another song I wrote last week", conjuring up a few chords on the keyboard, or just letting out the bleeding purity of that voice, she commanded attention. At the end of each song the applause could have shook the place apart. The animals move, somnambulant, through a landscape of bells and glass, tinkling underfoot; the wind keens. I’m searching for antecedents, comparisons, and I’m finding nothing. Maybe Scout Niblett if she played the synths. Or Jessica Rylan if she sang her confessional poetry as sleepy-time pop songs. Even these don’t fit. And to think Kate fucking Nash is number 2. There is no fucking justice. Hush, the buildings, they are sleeping now.

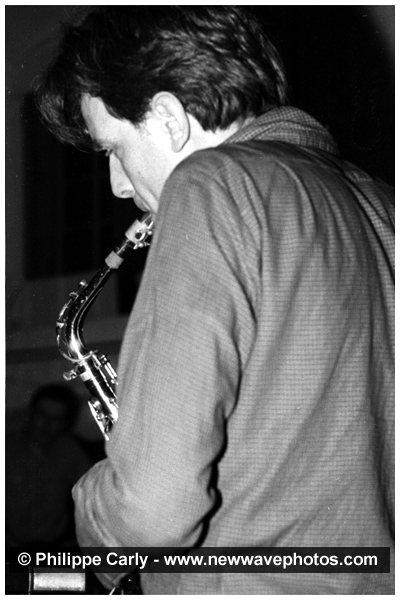

After that, I wasn't quite sure what to make of Blind Voyeurs. I'm normally orthodoxy-sniffing by the time any band sets up their instruments, and the presence of the usual guitar-guitar-bass-drums set-up (with the novel addition of DJ and keyboards) had me fearing boring rockism. Thankfully, their work was entirely elsewhere: wiry (and Wire-y) blasts of twisting, turning rock; disciplined, dramatic rhythms and guitar lines; psychedelic in the same way as OK Computer-era Radiohead; and, thankfully, mostly instrumental (the occasional singing, whilst nice, carried lyrics a bit too 'soulful white guy' for my tastes). The guitarist was an animated presence, fixing attention (and making photography near-impossible), even taking off his shirt halfway through for added effect (he excused himself with "It's warm.") The machines come full circle: electricity once again at the service of mankind, ripping up the air in the best possible manner.

Monday, July 30, 2007

Optimo In The Mix

Saturday, July 28, 2007

'Through A Glass Darkly'

Out of this stony rubbish? Son of man,

You cannot say, or guess, for you know only

A heap of broken images"

--T.S Eliot, The Waste Land.

Having just finished reading the third volume of Harold Pinter’s Complete Plays I’m probably more or less alone in saying that I don’t like his early work. Not that they don’t have their charms – from The Dumb Waiter up until 1969’s Silence they have a certain obscure power, derived from the arbitrary circumstances, the sudden shifts in character action, the opaque reasoning behind narrative choices. The plays set up sites of potential, a spectacle loaded with menace simply because anything could happen in the next half hour. David Lynch’s work carries the same sparking charge, but obviously on a much larger scale, because of the much wider and deeper possibilities of his medium – he can literally, as in Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire, construct his own free-floating realities by verity of the camera lens (film being the medium, and Hollywood the place, where the fantastic happens.) Pinter, who hasn’t written a new play for almost twenty years, is now counted as a National Treasure, the sign of a sure creative endgame (Larkin was counted a National Treasure around the time of ‘Aubade’, and never recovered from it) – but those early plays show an explosive route out of the dead-end of both conservative censorship theatre and late ‘50s Angry Young Men-ism, that didn’t resort to the puerile flesh-for-its-own-sake tactics of the hippies and the Tynan set.

By disintegrating the unnecessary aspects of plays – narrative exposition, psychological motivation, the usual comprehensibility to the audience, as if the audience weren’t people on the other side of the footlights but omnipotent spectators – he opens up spaces that hypnotise by themselves; his is a theatre of lacunae. In The Homecoming, the peak of the early plays, the frequent silences, pauses and wordless movements ratchet up the tension; the sudden bursts of violence, venom and desire hang free. The air is humid, dripping with sex and cruelty; each awkward silence opens up another gap between characters, makes the idea of a happy family and ending further and further. The progress is not so much one of narrative as of atmosphere, the pressure of a storm gathering in the accumulation of weight in the silences, lurching from fragment to fragment – things like Lenny’s anecdote about his potential murder victim "falling apart with the pox" or Max’s beating of Joey seem serve no purpose other than to disconcert and worry the audience. Uncertainties are introduced for seemingly no reason – such as whether the question of whether Teddy really is a Professor of Philosophy – other than, I assume, to undermine any sense the audience might have of questions being answered. No-one on the stage is really anything that they appear to be – a Verfremdungseffekt of sorts.

Revolving around Hirst, a hubristic, alcoholic writer (probably a bilious portrait of Pinter himself), the play seems better for the slight concessions to comprehensibility. Like The Homecoming, the characters’ relations are easy to pick up, and their identities relatively stable (the only exception being the apparent double identity of Spooner, may or may not be Hirst’s old school chum, Charles Wetherby.) The discrepancies in the accounts of the characters – which Pinter, by this point, no longer tries to call attention to as he did in the very early plays – are aspects of themselves, the results of growing old, beyond the point where the truth can still be faced without horror. The characters have lost any dignity or existence beyond what they can construct, beyond what they tell us from the stage. The question of whether or not Hirst knows who Spooner is when he wakes from a drunken crawl, or whether Spooner actually does have a wife and children in the country, ultimately don’t matter. The actual characters are spare but incandescent presences, cutting shapes in the semi-blackness that covers the stage most of the time. The occasional use of verbal imagery is spare and foggy, filtered through the cataracts of memory and the uncertainty of dream – searching, searing like lasers, but glimpsed like flames through fog. A good counterpart to this would be some moments in Sam Beckett’s mid-‘50s work: the images in Malone Dies, for example, where he sketches out, in bare words, the gorse fires on the hill he watched as a child (an image excerpted from Beckett’s own memory); the image, precisely because of its bare, befogged nature, forms so powerful a pull on the imagination. (An aside: this is precisely what I love in a lot of music – shoegaze, the calmer, more dubbed-out end of electronica (I’m thinking of Burial, or Porn Sword Tobacco), and some modern classical such as Penderecki, Morton Feldman or Arvo Part. Dean Wareham’s guitar solos on Galaxie 500 classics like ‘Fourth Of July’ and ‘When Will You Come Home’ exert such a magnetic pull precisely of because this contrast between their viscerality and the sea of distancing reverb in which they swim.) It reverses the usual Pinter formula of a threatening presence constructed from fragments like some fucked-up Merz construction: the stage is a yawning void into which the characters stumble, numb with drink, refusing to speak but not being able to face anything else; the silences are now simply the nothingness exploding into sight where it couldn’t be filled, the state of ‘groundlessness’ that Shestov discussed (aph. 17), the momentary acknowledgements that what we see before us is the icy, unchanging no-man’s-land of the title, the sense of tension and terror manifest in the silences making it clear that none of the characters want to be there, and neither want to, nor are able to be, anywhere else.

Friday, July 27, 2007

Regression In The New Tropics?

(Via Tim S)

(Via Tim S) "Of course, being a leisurely stroll away from the Thames Barrier (and have I ever been more thankful for this fantastic parade of steel and concrete crustaceans, rising majestically out of Charlton to provide the capital’s salvation) my own patch of overpriced asphalt and brick is entirely unaffected, as yet, though whispers about how one shouldn’t drink the water have been going around."

--Owen Hatherley.

Thursday, July 26, 2007

Shout-outs

Closer in time lies the Forbidden Planet night at The Portman, where the ever-excellent Skitanja, and Planet Monkey (Random Loop Generator's circuit-bending project) will be playing, along with a DJ set from the warped Language Timothy!.

Sunday, July 22, 2007

Quote Of The Day

Saturday, July 21, 2007

Reck The Place

Portman Hotel, Bournemouth

After the break the lights were dimmed and the way prepared for Cylob. He seemed to be the main draw of the evening for the scattering of ex-ravers in the audience, synapses long ago burned out by Ecstasy. There were, luckily, only a few, leaving the rest of us to get on with the business in hand: faced creased with attention over his laptop and mixer, the speakers filled with a restless, humming collage of digital acid squelches, submarine bleeps and maddened beats. And he kept going with that. And on. And on. Being on Aphex Twin's label, Rephlex, I wondered whether his intention was to simply tire the room's populace into the grave - I've never before seen one man reduce a room of grown men (and, indeed, the ladies - a couple of whom kept Cylob company down the front) to flailing, sweating wreckage. It happened, and I was in it. The life-threatening imperative - "dance, sucka!" - was too strong to resist, and I almost thought the venerable floorboards would crack when he suddenly added a volley of jungle beats to the mix, or slowed down the top layer of beats to a dubstep slowness. After what seemed an age, air a haze of sweat, he marched off, triumphant.

Tuesday, July 17, 2007

Documents Of Barbarism

"This side of the socialist revolution, the revolutionaries are a minority."

"This side of the socialist revolution, the revolutionaries are a minority."--Unknown speaker, sampled on The Redskins’ ‘Lean On Me’.

Up to Tolpuddle on Sunday for the final, rain-soaked day of the Martyrs’ Festival. What with my bag being flooded by an errant water bottle, not having enough money to get a copy of Benjamin’s Illuminations (how are the workers meant to educate themselves when 300-page paperbacks still cost £16.99 a pop?) and running into some guys from school (a couple of whom I’d had pinned as neo-liberal thugs) – including my former Politics teacher – to whom I felt completely not up to speaking, I spent most of the time in my usual catatonic state. The usual rum crew showed up – the NUM, the SPGB, Free Palestine, the SWP and the British Communist Party (or was it the Communist Party of Britain? I can never remember) – and a few unexpected faces – the Bournemouth West and East Labour Parties (who I thought were a myth), the Irish Republicans (in the form of the Troops Out Movement), CND and Respect. As always, the speeches were made – Tony Benn making jokes about his pacemaker – and the sets were played – The Men They Couldn’t Hang, Billy Bragg (who I was hoping would stop after ‘The Red Flag’ but had local schoolchildren come on for a doctored version of ‘One Love’ of all things – "Let’s drop the debt/And it will be all right!" They’ll learn, they’ll learn.) Whilst, admittedly, it was alright for a free concert – ‘you pays your money’, in this case none – I kept feeling they should quit the folk crap and put some grime on; notably, for a movement supporting anti-racism, I saw only a handful of black faces, belonging to an Indian migrant worker making a speech, and a sub-par reggae band doing a version of ‘One Love’ as I entered (what is with that song?) Stupidly, I forgot to bring along my Walkman, and The Redskins.

The Redskins formed in 1982 from the ashes of York anti-fascist hardcore band No Swastikas. They released their first and only album, Neither Washington Nor Moscow, 4 years later – an odd amalgam of amphetamined Dexys’-style Northern Soul, punk, early James Brown and unreconstructed SWP rhetoric, it’s one of the few explicitly political albums from that era to have weathered the ravages of time. At the time they were darlings of the music papers, but are now barely remembered – where their sometime touring partner Billy Bragg is allowed to record tepid folk albums and publish books at will. The album seems, now, like an artefact, a time capsule playing the same recording over and over – almost the entire album is concerned with the miners’ strike that swept up the band; they relentlessly performed benefit gigs, and ‘Keep On Keepin’ On!’, released October 1984, formed a key part of the soundtrack to the strike. That summer, playing ‘Keep On Keeping On!’ on The Tube, they had invited one of the Durham miners on stage to make a speech; in a wonderfully symbolic moment, the microphone instantly cut dead. It was to prove prophetic – after the end of the strike they released a few singles, performed a benefit tour for the ANC; their penultimate single, ‘The Power Is Yours’, was a mournful look back at the strike ("We blew it…"). Soon after, the band split and frontman Chris Dean disappeared to Paris, becoming largely a recluse. The failure of the strike had clearly broken him – to The Redskins, as to the rest of the SWP, the strike was the first stage of the "crisis of capitalism", nothing less than the beginning of the end of history.

All this seems almost ancient in 2007’s neo-liberal Britain, where there is no past unless it serves the purposes of ruling-class ideology (e.g. the Second World War, in which ‘the Blitz spirit’ and our defeat of the ontologically Evil Nazis are meant to serve as justification for the War On Terror), and no future, nothing into which to project the desire for a better life – an economic model based on infinite growth in a finite world can never provide one - a world where ‘a better life’ means longer hours for more commodities, and all other options are closed down, and ‘this is the best you’re going to get’. When you reach the end of history, how you got there ceases to matter – the logic of Leninism translated into the language of Kapital. The Socialists are famous for holding onto the past with both hands, guarding a history no-one knows, a litany of names and dates – Haymarket, the Martyrs, the Winter Palace (1905), Petersburg (1917), the Ukraine (1917), Kronstadt, Barcelona (1936), Budapest (1956), Paris (1968), and, I would wager, Yorkshire (1984) – guarded by melancholics, pub-squabblers, bronchitis cases, visitor centre staff, (and Billy Bragg, who signed my copy of Neither Washington… during my last visit to Tolpuddle). Sometimes snatched from the jaws of victory, sometimes doomed from the start, the failures and grand and small haunt the movement, leading to what Benn called "Left pessimism… ‘Oh, we’ll always be betrayed, everyone will betray us.’" We come up, again, against the limits of historical materialism: ‘the inevitable victory of the proletariat’ was, from the beginning, the guiding historical idea of revolutionary socialism; even by the time of the Bolsheviks, you can see the rhetoric changing from ‘inevitable victory’ to ‘victory by any means necessary’; by the time of ‘Lean On Me’ it was "Success comes to the strong/The struggle’s hard and the struggle’s long". By 1994 the Soviet project had finished, and social democracy, the compromise between labour and capital, was the only option going. The idea that historical materialism, in its deterministic Marxist form, was false was perhaps the end of the revolutionary project; nowadays the SWP and the trade unions demand an end to "Brown’s Pay Freeze" and longer coffee breaks. Anyone with more than reasonable demands would seem to have one option: that of Guy Debord, who had published the fatalistic Commentaries On The Society Of The Spectacle in 1989, then killed himself five years later.

And seeing as Chris Dean hasn’t been seen for years, it’s possible he took that option. It would be an ignominious end for The Redskins, just as Richey Edwards’ was for The Holy Bible: the album seems to have been sequenced almost ironically, beginning with the relatively short ‘The Power Is Yours’ and ending with the enormous, astounding second single (released before the miners’ strike) ‘Lean On Me’, going in exactly the opposite direction to what one would expect; in spite of the history, it’s incredibly fierce, determined, 43 and ½ minutes of passion and funk; music in which ‘soul’ – the possibility of transcendence, usually through the gooey medium of ‘love’, in swelling strings and yelping voices – becomes an expression of the immanence of revolution: love songs for solidarity. Possibility is the record’s voice, the whispered sentiment: their final single, ‘It Can Be Done!’ reels off the history of the Bolsheviks, the Spartakists, the Spanish Communists, counselling to "learn a lesson from your past"; in ‘Take No Heroes!’ Chris Dean, with at least one eye on posterity sings that "A man may die/But his dream survives."I hate to use the word ‘hopeful’ as anything other than a perjorative, but it almost is. You can see how something like this could be seen as merely your standard nostalgia-fetish for Communists, a dewy-eyed reminder of the days in which (they thought) they could bring the country to a standstill. But that’s not quite right: there’s something bizarre and mercurial about it that goes beyond the mere burden of circumstance, a voice, as Walter Benjamin wrote "exploded out of the continuum of history".

At this point we begin to enter murky territory: Benjamin was as much a mystic, a theologian, as he was a proper rubber-stamp historical materialist; the ‘Theses On The Philosophy of History’, written very shortly before his death, pursued by the Nazis, read like a lost scrap from the Dead Sea scrolls, treating history as a tangible inheritance (as, he notes in the final thesis, the Jews were taught to treat their past through the preservation of the Books Of Moses and regular prayers), an abstract, Gnostic quantity, instead of as simply a collection of events and the narratives constructed around them. As Benjamin himself notes, "’historical materialism’ is always supposed to win. It can do this with no further ado against any opponent, so long as it employs the services of theology." The kind of theology Benjamin had in mind was not that of Stalin: a Roman church built around atheism, in which the terms of God, Nation (Mother Russia), State and the Leader (in the form of Stalin, but also Lenin, of whom he had huge numbers of statues built; the personality was a function of the archetype, not the other way around.) His theology was older than that of revolutionary socialism, whose sense of history operated in messianic, Christian terms, with its Golgothas and meek inheritors; it was the theology of the 40-year desert wanderer, the casual miracle (the clocks stopping in Paris just as God made water flow forth from the stones), the black shrouds of grief and the endless living, waiting. (Only the Jews could have come up with the Passion, but only less perceptive minds would have made those three days of minor agony redemptive. For the Jews, the crown of thorns is never removed, the nail remains in the hand. A lifetime of dull agony.) For Benjamin, the Jew not merely wandering away from his theoretical Heimat (Israel) but from his ‘homeland’ (Germany), "the future did not… turn into a homgenous and empty time… in it every second was the narrow gate, through which the Messiah could enter." By an act of faith – the kind of faith, as Kierkegaard and Shestov knew, can only come when your back is up against the wall – he moved past the limits of historical materialism (just to note, I know he was a secular Jew, a confirmed materialist. But even within the materialist worldview, it is possible to sympathise with certain aspects of religious feeling: prioritising certain aspects of existence (such as suffering), or treating material existence in an abstract manner, as a system of signs and tropes charged with significances. This is exactly what Benjamin does to make the leap beyond materialism’s dull bounds.)

The voices of the past exist in a symbiotic relationship with the present, "a secret protocol" which gives every generation, tied to the burden of its predecessors – just as the prophets prefigured the coming of the Messiah – "a weak messianic power", able to bring about the redemption, the resurrection, of all that once was, both remembered and forgotten. Artefacts like Neither Washington Nor Moscow, the replica ‘Coal Not Dole’ one can see at Tolpuddle, are not nostalgia items precisely because they are not reminders of the wounds of the revolutionary movement, fetish objects for self-pity, but of what people found in the conflicts; the old clichés like ‘community’ and ‘solidarity’, exactly what the non-society of post-Thatcher Britain sneers at: the students holding off the police and the workers sealing the factories in May 1968; the gangs of Budapest kids, controlled by workers’ councils, commandeering Soviet tanks in October; the scenes in David Peace’s GB84 (I think the main one was of the Battle of Orgreave), in the miners’ ongoing story (written in Yorkshire demotic) before they really join battle with the police ("We’d fuckin’ have ‘em, this time.") The voice rewinds and plays again in unchanging fragments of a present that had slipped out of touch, but not out of mind: "they reach far back into the mists of time. They will, ever and anon, call every victory which has ever been won by the rulers into question." The Jews – or so Nietzsche claimed – revenged themselves on the Romans, who organised a spectacular history of successive Emperors, an "empty, homogenous time", by making every event of the past point to the birth and death of a scruffy carpenter, "the vanquisher of the Anti-Christ." The points at which history as the writings of the victors, the ruling-classes, ruptures – at which, as Greil Marcus wrote, the individual and collective become "the subject, and not the object, of history" – (Zurich, 1916; Berkeley, 1964; May 1968; London, 1976-1979) become the points from which new narratives can begin, from which we can start making history up as we go along: "he cognises the sign of a messianic zero-hour of events, or, put differently, a revolutionary chance in the struggle for the suppressed past." Benjamin, just like the Situationists, understood that theory and strategy don’t change anything much; the emotions of the common man, the fealty we feel to the past, the scars from coal dust and police batons, the sickened disgust we feel for a world drained of dignity, in which greed and ignorance are the prime virtues, are what will build the future we want. ("Simply by stating ‘No Future’, the Sex Pistols were creating one." Record Mirror, quoted in England’s Dreaming.) Tony Benn was wrong when, on Sunday, he quoted one of the Cuban revolutionaries: "Our revenge will be the laughter of our children." "The ideal of the emancipated heirs", the fallacy of reproductive futurism, means nothing; only the voices of the dispossessed (including ourselves) can nourish dreams, the alternative on the other end of the Northwest Passage. Why should we work for our supposed children when things are fucked up for us?

Consumer capitalism can only exist if we treat "it as a historical norm", if we accept it as ‘common sense’, and "the tradition of the oppressed" teaches us it is otherwise. The revolutionary impulse – "I am nothing and I should be everything" – the cry of all the dead voices of the past, what is felt every day as we are shunted around the desert of capital, is genuine, and what we must stay true to. Despite the necrophile tendencies of the Tolpuddle set, it’s surprisingly heartening to see that some still halfway care. On this side of the socialist revolution, the revolutionaries are a minority. Afterwards, if we ever get there, they won’t need to be counted. "Only for a resurrected humanity would its past, in each of its moments, be citable. Each of its lived moments becomes a citation a l’ordre du jour – whose day is precisely that of the Last Judgement."

Friday, July 13, 2007

"It's A Beautiful Night..."

-- Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Been a bit distracted the last few days (by what?), didn’t get round to writing about it, but I finally saw Scott Walker: 30 Century Man last Saturday. Very good in terms of the footage it got – marvellous stuff from the studio during the recording of The Drift – but really got on my wick at the start: the usual correlation of Walker with the Orphic myth, the poet descending to the underworld. The media perspective of Scott swings between the two extremes – the ‘isn’t that weird?’ Mojo/Word view, relying on novelty value; and, on the other hand, the fawning, hyper-academic Wire viewpoint, in which the technical verities of the music become the sole salient point. Both completely miss the point of Walker’s late music, focusing on the avant-garde elements: his work is, really, an extension of the torch song tradition, only one where the music has changed to meet the demands of the Song. Just as in the torch song, the words cannot be translated as just the author’s viewpoint, correlating the authorial and narratorial ‘I’; if that were the case, the great singers like Sinatra or Ella Fitzgerald would be wrecks (we won’t mention Billy Holiday) – songs are transposed from singer to singer, the singer merely provides the voice to articulate the sentiments. As Walker himself says, it is "just a man singing" – working on the same axis as Sam Beckett and Morton Feldman, at the difficult and paradoxical task of producing "lessness", of making silence. (He could also be compared to the Hungarian poet Janos Pilinszky, who had a similar time-to-output ratio: six books in 34 years, many of the later poems being little more than couplets.)

On The Drift, silence plays an important part, becoming the space from which the voice emerges, at times fraught and stiff like a rabbit from its hole; sometimes, as at the end of ‘Jessie’, an operatic soaring from the void: "Alive/I’m the/only/one/left/alive." Interestingly, there seems to be little of this supposed ‘real’ silences on the record: even when there is no visible (?) musical activity, a background hum of electronics or manipulated guitar marks out the music, gives it presence, preventing the listener from ignoring it – a technique used by Gyorgy Kurtag, the ‘Mr K’ whom he thanks in a note to ‘The Escape’ (who was also a fan of Beckett, and made a number of pieces based on his texts.) The avant-garde flourishes – such as the, um, unorthodox percussion used on ‘Clara’ (the notorious side of pork) and ‘Cue’ (the BIG BOX, captured in all its glory on the film), or the use of atonal string drones - serve the song rather than the other way around; he has to go out to the edge of musical expression – severing the connection between instruments, preventing ‘groove’ (co-conspirator Peter Walsh remarks in the film that during the recording of Climate Of Hunter "the melody remained a closely-guarded secret"; the musicians are not given ‘click tracks’ or guide vocals), abstracting instruments away from their usual sounds, textures and playing mode – because he goes out to the edge of linguistic expression – among those in the no-man’s-land occupied by Celan, Beckett, Blanchot, Emil Cioran (to a certain extent), Pilinszky, Sarah Kane, Harold Pinter (in his decent days), the cracked prophets in Iain Sinclair’s Conductors Of Chaos anthology (especially Brian Catling), where the entropy grows so great, the signal so weak, on the threshold between life and death, between where nothing is worth saying and where nothing ever can be said anymore.

I don’t pretend to know what large amounts of Tilt or The Drift mean, and I suspect that the excavation of every line would require the usual ‘a thousand geeks at a thousand typewriters’ trick (or as it’s better known, the Internet). It’s also, perhaps, just better to leave it as it is: the outward mystery at the core of a lot of Walker’s work is far more compelling than the easily-explicable works of a hundred songwriters, just like the enormous hole in his public biography (between about 1969, with Scott IV and 1978, with Nite Flights) is more interesting than most (and also prevents crass ‘biographical’ readings of his work.) The references one can catch – to Kabbala, Elvis’ twin brother Jessie, Adolf Eichmann (on ‘The Cockfighter’ from Tilt), the Srebrenica massacre – and the bits of what sounds like musical method acting – the ‘pow, pow’ on ‘Jessie’, the wailing voices on ‘Hand Me Ups’, the Donald Duck impression on ‘The Escape’ – meld together in an almost mystic, obliquely appropriate way; he’s going beyond the usual bounds of language, almost beyond what can be spoken, what can be made into music, groping for words where he can get them (music hall songs, ‘I Wish I Was In Dixie’), abstracting songs into collections of drones and sounds. As The Drift progresses toward the end, the characters seem to get weaker and more fragmented, like Beckett’s Malone, until, on ‘A Lover Loves’, it’s just spare guitar, a tiny, broken voice, that conspiratorial hissing; bittersweetly, only at death is "everything/within reach."

It’s easy to see why Walker seems to carry the image of a reclusive genius, a kind of sonic monk: he’s much more talkative in the interviews than you’d expect, especially when chatting about getting drunk with Playboy bunnies in the Sixties, but it’s apparent he’s really uneasy talking about his work; hesitating, fidgeting, trying, shaking with intensity as he answers; you suspect he never quite succeeds in explaining himself to satisfaction, that the latter-day work is as oblique to him as it is to many listeners. By contrast, in the performance footage of ‘Rosary’ he looks almost possessed, neck muscles jumping out; it’s as if he has no connection with the song, apart from putting together the parts – he says that he’s unable to force the creative process, that "You have to let it come to you"; a shamanistic channelling (of which we can see parallels in Ian Curtis), an auto-critique of the metaphysics of presence, a text without an author, a collage of voices detached from context, without origins. "Just a man singing." In that sense it makes it very difficult to write about, because the textual elements elude all the usual constraints and organising principles of writing, making the usual techniques of analysis and explanation redundant. (The film tried to get around this by supplying abstract visuals to accompany them, or have shots of people – well, David Bowie – listening to the records.) If there’s no permanence in the text, no author to speak of, no identity from which the words emerge, then the words are simply floating free, trickling down the pages of the CD booklets like concrete poetry. It’s at this point we start to overlap with the territory of Blanchot and Derrida: speaking the unspeakable, voices speaking out of silence, and going back to silence. In that sense, both Walker and the post-structuralists were children of Kafka, who, as Mark K-Punk notes, writes about "not a world of metaphysical grandstanding but a seedy, cramped burrow"; there’s a distinct sense of claustrophobia in the texts, paradoxes and difficulties, mortality, desolation and disease, the sheer awkwardness, the difficulty of material being, hemming you in; there’s something ineluctable, something neither you nor the voice can get past; an abandonment of the pretense of explicability, of the belief that words can really explain anything. The film ends happily - with Walker et. al fantasising about 'the next album' (whenever that's going to happen) - but it still felt like an anti-climax. It's idiotic to assume that 'explanations' could be found in a documentary, but it would still have been good: simply drawing attention to the oeuvre wasn't enough, as far as I'm concerned. I was simply left with the Grant Gee photos of Walker, rendered into static, the music from 'Face On Breast' playing over the titles as I left. Despite everything, you still have the urge to look for explanations, to try and grasp, to try and see behind that image. But it's irreducible. Silent.

Wednesday, July 11, 2007

Future Primitive

In 1979 The Pop Group released Y, recently re-released after being out of print for over 20 years, its unavailability making it one of the most talked-up records of the post-punk era, something like the band’s Great Artistic Statement compared to the hectoring, over-conventional How Much Longer Must We Tolerate Mass Murder (and even the too-direct but still excellent ‘We Are All Prostitutes’). The post-punk revival of the last 4 or 5 years (‘House Of Jealous Lovers’ was in ’03, right?), combined with the nostalgic interest of a generation of sweaty middle-aged men (and curmudgeons-before-their-time such as myself) in the punk explosion and its riotous aftermath up to 1981 has created an enormous fetishisation of the products of that near-mythical time, and raised this album’s stock to terrifying levels. The legendary story of the Pop Group - a tale of teenage romance and intensity, intellectual fervour, and "really excellent record collections", as documented in John Mulvey’s new sleevenotes – adds a further frisson to the artefact – all that talent couldn’t have gone nowhere, logic says.

The cliché for journalists forced into writing about the album is that "the band sound like they’re playing five different songs" – and, most of the time, it is quite obvious this is bullshit. The Pop Group put the smack down on Rule of Rock ‘n’ Roll #2: ‘The band is one unit, all playing one song’, but in no way do they sound disunited. On opener ‘Thief Of Fire’ (discounting non-LP single ‘She Is Beyond Good And Evil’, stuck mysteriously at the beginning), the band’s separate elements – Mark Stewart’s animal shrieks, the funk rhythm section, Gareth Sager’s non-linear chicken-scratch guitar – play in the proper muso fashion, except for being very slightly out of alignment, a consequence of the band’s extremely primitive musical abilities and the reason for subsequent and annoying journalistic comparisons to Captain Beefheart (Mark Stewart has said "I couldn’t stand Captain Beefheart. We thought we were like Bootsy Collins or something.") The song’s gradual slide out of any semblance of ‘time’ into a nightmare of sax blurts, tape noise, rhythm and Stewart’s voice seems closer to a strategy than an accident: by refusing to train to a muso level before playing songs, the band avoids the 4/4 stasis macho white rock rhythm and aligns with the avant-garde tradition of stripping away musical clichés that began with the development of atonal music. The music sounds, more than any work of that time, unsure: at times, such as on ‘We Are Time’ it sounds like the music might shake itself apart with the fragile intensity of the playing; bass or guitar drops out, instruments stretch out, swoop in volume, speed up on tapes, fragments coming at you from all directions in some cavernous dub nightmare; Stewart’s utterly untrained voice drips with dread even as it shrieks and hollers, being swamped and silenced in feedback at the end of ‘We…’. And after all, to achieve that kind of effect takes far more effort and imagination than playing in time. What’s more, the album follows the principle of discontinuity even further, seeming to take in Burroughs’/Gysin’s cut-up principle in its collage of influences (dub, funk, Cage-ian avant-classical, punk, free jazz), the editing employed by Dennis Bovell and the band (requiring hours of tape splicing, reconfiguring the linear, twisting time to create a cubist soundspace like Burroughs’ own tape experiments) and seemingly semi-anticipating the musical collisions of hip-hop (notice the breakbeats in ‘Blood Money’; hip-hop was to be a major influence on Stewart’s experiments with Adrian Sherwood at On-U Sound).

Of course, the album isn’t all to be praised. The piano tinkling and singalong humming on ‘Snowgirl’ calls attention to the rather piss-poor lyrics (and yeah, I know the connection to Cecil Taylor and John Cage, and they’re very worthy, but it won’t save them); ‘The Savage Sea’, whilst a very pleasant piece, doesn’t really play to their strength (and the lyrics, when you can hear them… ow), and is over too quickly. ‘Don’t Call Me Pain’ starts off promisingly, then slows to a bizarrely sluggish pace , never really taking off again (and I swear that sax riff is lifted from ‘Hey, Big Spender’). But these things are partially to be expected: this is the throbbing heart of the original Pop Group project, an attempt to put the wildest collisions of theories and energies into practice, a grand experiment in sound; a musical leap into the void, the sound is sundered by the same energies that glued it together. Possessed of no musical ability, the band set out with more musical ambition and imaginative power in Gareth Sager’s thumb than in Yes and ELP’s entire careers. Combined. By an odd combination of accident and design, the band had clawed the idea of the ‘musician’ back to its barest, most nascent form – a reflection of the band’s celebration of primitivism, manifested on ‘Words Disobey Me’. (Incidentally, if anyone has any info on the Mud People of Papua New Guinea, featured on the sleeve, I’d be grateful – I can’t seem to find anything on them.) I feel loath to suggest a kinship with outsider music, but the band seems to invite it: "Culture is work and duty in the West, and anything natural is a crime", Gareth Sager told the NME. A better idea would be look at these ideas as anti-imperialist strategy taken to its logical conclusion: not merely siding with the victims of colonialism, but deconditioning, the destruction of Western culture’s grip on the psyche of the band themselves. It’s a sign of necrotic stupidity to assume that black music forms are connected to the African utopia (see the concept of jazz and blues as "primitive" music in the 1920s) the band talked about, but it’s hard not to note the addition Vaneigem gives to the above quote from Dauer: "The instant of creative spontaneity is the minutest possible manifestation of the reversal of perspective"; ‘discontinuity’ as the Northwest passage out of the bored fortress of capitalist music, into "the new innocence". By a year later, the band were encouraging people to ‘Rob A Bank’. Go figure.

These days Mark Stewart is making techno as Claro Intellecto, prepping a new album (apparently), and, no doubt, encouraging along the Bristol dubstep scene. He’s still involved in anti-capitalist activities, but I can’t help but think that he looks wistfully back on this as his greatest contribution to the cause.

Saturday, July 07, 2007

Martin's Reverie...

Portman Hotel, Bournemouth

After a considerable gap spent setting up equipment, all hell broke loose as Skitanja came on, masked, wigged and dangerous, powered by laptop gabba beats, overdriven surf-rock and seemingly completely untrained trumpet blasts from their drummer. Meeting complete incomprehension from a certain number pint-nursing meatheads with their first song (composed mostly of barking through their lady-masks), they quickly got into the swing of bringing their rock elements to the fore, guitarist Steve Potatoes bringing forth a massive cloud of duochord thrash, Sonic Youth levels of feedback powering along on the back of both laptop and drummer going at full pelt, then doing an immediate stylistic u-turn mid-song, guitar twiddles mixing with the odd percussion (the drummer/trumpeter used a maraca to hit the drums, that broke halfway through), until another shift brought the whole thing to a halt.

As for Flipron... Normally I don't like to speak ill of the dead, but I'll make an exception this time: if people haven't learned by now that rock 'n' roll is long dead, then it's obvious that 're-education' (threatening Soviet undertones intended) is necessary for the entire population. I got the feeling they were enjoying themselves, and the crowd seemed to as well. Keep in mind: "Madness is rare in individuals - but in groups, parties, nations and ages it is the rule" - Nietzsche. They did use an accordion on 'Hotel Rustique', though... Alright, they won't be first against the wall when the revolution comes.

Thursday, July 05, 2007

If You Tolerate This...

Even more odd to 2007 eyes is the Manics’ presentation: on ‘Motown Junk’ they wear ordinary jumpers, stencilled with the usual crude political slogans; in 2007 they would be expected to be decked out in the very latest, most ridiculous fashions; their resurrection of glam’s gender-bending and theatricality seems so utterly weird compared to contemporary ‘rock ‘n’ roll’’s obsession with ‘authenticity’ and the boring, stodgy men who apparently personify it. Looking at these things I didn’t see the first time round, it seems that the Manics were the last great chance music had of dynamiting the rock ‘n’ roll myth, a mission they took on from punk and post-punk – girls were just as much (if not more) a part of their fanbase as boys; intelligence had just as much to with their music as sweat. Their cold, destructive dynamics, the deathly negation of their sound, made probably the biggest hole in the spectacle since the Sex Pistols; you could think of them as the last chance we ever had of wrenching the means of expression back from the ‘official’ culture, of stealing ‘rock’, like the Promethean fire, away from the corporations and the middle-class.

I don’t know, is it stupid to mourn for a cultural moment you were never part of? The history of music is too littered with examples of brilliance and cultural autonomy – 60s free jazz, the Crass collective, post-punk and the DIY explosion, early techno and rave culture, riot grrrl, jungle and garage – to completely despair, but it seems that’s the only course of action when there’s literally over 100 million bands on MySpace and at best a handful of decent things to listen to, and when independent labels are giving rise to stuff like this, rather than stuff like this, when all sense of importance or value seems to have disappeared from music. (There is, of course, the whole thing of music becoming so prevalent it has changed into aural wallpaper, something k-punk has argued is a central point of sonic hauntology – but that for another time, perhaps.) In fact, the Manics seem to have made this point well enough themselves – one can’t help but feel their slide after Everything Must Go was the result of a sense of waning importance, the realisation that the revolution had failed, and, like all failed revolutionaries, they were to forever lurk, embittered, in the shadowed sidelines of history. It's this that lends such a heartbreaking poignance to a lot of their later work (which, I have to admit, I was too harsh about. Oh well.)