"People still hate each other, they just know how to hide it better"

The first in a(n occasional) series of posts about the films of my adolescence.

You don't know till afterwards why you cared. The art that attracts you in your teenage years - when our engagement is at its most fresh and frantic; the art that lays the co-ordinates of your taste - comes, at its best, as a surprise: strange, shocking, shaking, a sensation registering for the first time. But its resonance, unlike its unfolding experience, doesn't come from nowhere: in some sense, you were meant to see, to hear, to read these artworks; there was something in you with which they registered - not simply at the present of viewing, but in the multiple versions of you that reside in your past, and will shift and unspool into your future. Iain Sinclair isn't wrong when he calls films (and, I would add, records) "implanted memories": they come to haunt us anew with the passage of time, unfolding beyond their runtime; you come to recognise that they were a part of you, and you hadn't known it until then.

When I first saw Ghost World, films weren't shown on TV as soon as they'd finished their theatre release (my taped copy has adverts for a showing of Bring It On the same week), and Channel 4 still sometimes showed interesting movies. I'm convinced I was still in 6th form, but couldn't say which year. (I know this only because I remember reading the comic book by Daniel Clowes a year or more later, when I'd graduated and was unemployed over the summer.) This was only just after we'd switched to a DVD player, rendering useless all of the VHS-taped films I'd gotten into the addict's habit of watching (Vanishing Point, 8 1/2, Taxi Driver, The Man in the Moon, etc.) It became one of my staple films to bore friends with; I watched it repeatedly (by) myself. Which is surprising: the only things that really registered were Enid (Thora Birch) and Rebecca's (Scarlett Johansson) sense of disdain for the claustrophobia and stupidity of high school, something which occupies only about the first 5 minutes of the film; neither could I feel smug about getting the film's reference-points (I didn't listen to jazz then, nor to very much blues), although the comic book, with its repeated references to Sonic Youth and the Ramones, did rather better for that.

In a certain sense Ghost World is an answer to the high school film, with its flattened emotions and caste-system certainties that in fact reflect the narrowed worldly parameters (and straight-up thickness) of teenagers - the anti- or post-high school film, beginning where they end (prom and graudation). Enid and Rebecca mirror this in the narrowness of their friendship: at the beginning it really is just the two of them, against the world, united in a negativity that Rebecca seems to be already slipping away from. They're thrust into a(n adult) world that has no place for them, that fulfils none of the promises - of freedom, of empowerment, of satisfaction, outside of the cloistered world of high school - that it advanced, that can only make demands. Teenage disaffection turns, in Enid's case, to bafflement and a disgust, tempered by cynicism, that eventually tips into despair at the absurdities that adults advance upon them as the preconditions of carrying on living - as in her one day of employment on the popcorn stand: "You don't criticise the feature!" "What, it's my schtick?" "A world", Camus writes, "that can be explained even with bad reasons is a familiar world. But in a universe suddenly divested of illusions and lights, man feels an alien, a stranger." Thus Enid and Seymour: united by a sense that the world will not accommodate them, that it has systematically refused them any possibility of a relationship with it; that it is not as it should be. (Whereas Rebecca, with her well-adjusted good looks, is perfectly able to slip the role she had as one half of Enid's disaffected pact and assume another, as the cute coffee shop girl - as the Wikipedia article on Ghost World puts it (euphemistically), she "matures into a sensible young woman".) The overlit suburbia the girls drift through is recognisably the world of Daniel Clowes' comics - the estranged expanses of Ice Haven and David Boring, normal and conformist to the point of breeding malign weirdness, where inexplicable things occur and patches of grotesquerie break out like rashes (cf. the 'Satanist' couple in the cafe in Ghost World), colonised by anonymous strip-malls, multiplexes, chain coffee-stores, fake 50s diners. To such an unsatisfying phenomenal world, Enid and Seymour are ghosts: observers, unable to participate in its life, who are themselves seen only out of the corner of one's eye - remember how they only come into contact with Seymour by pranking him, accidentally seeking him out; cut up outside Wowsville, he hurls curses at the driver, a sign of a man perpetually ignored - "this kind of thing must happen to him all the time".

There have, of course, been more than enough documents of teenage alienation - the nineties, when Daniel Clowes first drew and published Ghost World (serialised in Eightball), was chock full of them. But Ghost World is set apart by the dryness and the economy of storytelling Terry Zwigoff brings to it, that neuters any tendencies to, on the one hand, sentimentality or self-pity (about the vanishing of youth, the 'preciousness' of adolescence, etc.) and, on the other hand, stupidity in its relation to the adult world, neither accepting any quarter with it nor elevating its protagonists into heroes for resisting it. It's unsurprising that Clowes apparently wanted, in his artwork for the comic, to make the same subtle use of period signifiers as Catcher In The Rye - Enid possesses the unclouded vision and snappiness of mind, but also the same dispassion and sense of unfillable lacks as Holden Caulfield, but transposed into a female protagonist. Years ahead of indie movies that allegedly confronted the disappointments of real life (cf. Lost In Translation, 500 Days of Summer, etc.) Ghost World denied any sense of resolution or easy happiness to its characters, whose not-altogether-comfortable worlds become (as you would expect, in the nature of drama) upset, but don't reconstitute themselves in anything but the most unsatisfying forms - Rebecca as the conformist barista (though she seems unperturbed by that life, her rightful inheritance in a sense), Seymour, bereft of both Dana and Enid, Josh denied the ambiguous possibilities of a relationship the comic suggested, and Enid departing for what might well be the afterlife. Ghost World is the only film I know of where the characters remain, by the end, unredeemed. There's a terrible and brilliant clockwork logic by which all of the characters' possibilities of escape, of happy resolution, crumble away in interlocking patterns - of how they drift apart. It was only in the months, and years, after leaving school, abandoned to the same hopeless drift, coming back to it, that I grasped what freighted Enid's arc - that she was, as Anwyn says, speaking of Salinger's characters "struggl[ing] in every chapter... against their fear of becoming the person that might say: yes, this will do." Unlike most teen-angst films, it admits of the adult world, with all its frustration, impotence, guilt, disappointment but also its possible (if frequently strangled) possibilities and elations - of life not lived alone, of love not empty. (Enid's complaints about "extroverted, pseudo-bohemian losers" ("You guys up for some reggae tonight?") are, as I've learned at university, absolutely correct).

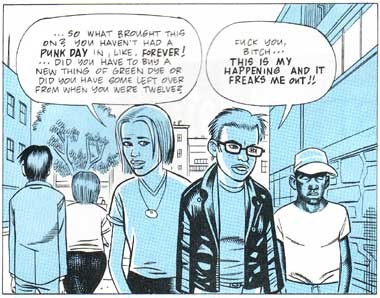

And of course, Ian Penman is absolutely correct about Thora Birch: she's not only far more interesting in her role than Scarlett Johansson, but far sexier - "And?, in real life?, that imperious cool bitch act of Enid's? It would totally have boys and men (and cats and dogs and eunuchs and aliens) totally at her big booty big booted feet." (My friend J., after he lost his virginity in Amsterdam, related the anecdote to me with the words "and she looked just like the girl in Ghost World". To which I answered "Wot, Scarlett Johansson?" At which point we both frowned.) One of the greatest and saddest ironies of Hollywood in the 00s has been the disappearance of Birch and the rapid ascent of Johansson (whose subsequent work, Lost In Translation aside, gives me little reason to feel she's receiving her just deserts in this): Johansson, pale, affectless and boyish with her shorts and throaty voice, made a template for every female cipher in the next decade of indie cinema (most of them played by her), where Birch, over the course of the film, constantly slips between subtle emotional gradations, conveying the sense of a girl unable to find what she wants, what possible identity or role she might adopt. She plays deadpan, cynical, defiant ("It's obviously a vintage 1977 punk look, dickhead"), desolate, overenthusiastic, whimsical (the delightful scene at Anthony's and afterwards), frustrated, tender and all the degrees in between. Her relationship with Seymour seems so believable precisely because of the sense of shifting and often paradoxical affections she conveys; you feel, indeed, that this is an substantial, autonomous person on screen dealing with the real flux of life and self. She condemns in advance the lifeless adolescents of Gus Van Sant's Paranoid Park and the marionette MPDGs who would soon populate indie cinema like a plague of boils. Enid's disaffection is also possibility - the opportunity and wish for authentic life so quickly and cruelly closed down. She's also the subject, as IP notes, of one of the great scenes about the power of music, as Skip James' eerie, androgynous voice rises up behind her through thick crackle, and, each time the track comes to its end, without saying a word she puts the needle back to the start - and almost the only scene to do so (convincingly) with a woman, "rather than some nerdy fanboy collector guy", refuting the idea, so often pushed in film, that music is a substitute for life, rather than another part of life - its richness, pain and possibilities. And love. Always love.

2 Comments:

I haven's seen it for some time, but I enjoyed it greatly, although I remember being unconvinced by how quickly Scarlett J and Thora H's friendship drifted apart.

Also, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and Garden State shouldn't be used in the same sentence, even though that's what I'm doing right now. ESofSM never pretends the central relationship is perfect. Garden State is one of the most repulsive films I've ever seen - and I'd be surprised if anyone had their life even slightly changed by The Shins.

Absolutely re. Shins; whereas, who wouldn't have their life changed by hearing the blues for the first time?

I really liked 'Eternal Sunshine...' the first time I saw it; I still think it's a wonderful concept, and very well-handled by Michel Gondry. The Kate Winslet character (you see, I can't even remember her name!) really nags at me, though, as she's so obviously not a real person, but a straight-up MPDG - fragile, quirky, non-commital young women w/ whom our protagonist is in love in spite of their flightiness are just not fun any longer, if they ever were.

Post a Comment

<< Home