Future Primitive

In The Revolution Of Everyday Life, Vaneigem, trying to describe the texture of life after the spectacle-commodity economy, quotes the jazz writer Alfons Michael Dauer: "The African conception of rhythm differs from the Western in that it is perceived through bodily movement rather than aurally. The technique consists essentially in the introduction of discontinuity into the static balance imposed on time by rhythm and metre. This discontinuity, which results from the existence of ecstatic centres of gravity out of time with the musical rhythm and metre proper, creates a constant tension between the static beat and the ecstatic beat which is superimposed on it."

In 1979 The Pop Group released Y, recently re-released after being out of print for over 20 years, its unavailability making it one of the most talked-up records of the post-punk era, something like the band’s Great Artistic Statement compared to the hectoring, over-conventional How Much Longer Must We Tolerate Mass Murder (and even the too-direct but still excellent ‘We Are All Prostitutes’). The post-punk revival of the last 4 or 5 years (‘House Of Jealous Lovers’ was in ’03, right?), combined with the nostalgic interest of a generation of sweaty middle-aged men (and curmudgeons-before-their-time such as myself) in the punk explosion and its riotous aftermath up to 1981 has created an enormous fetishisation of the products of that near-mythical time, and raised this album’s stock to terrifying levels. The legendary story of the Pop Group - a tale of teenage romance and intensity, intellectual fervour, and "really excellent record collections", as documented in John Mulvey’s new sleevenotes – adds a further frisson to the artefact – all that talent couldn’t have gone nowhere, logic says.

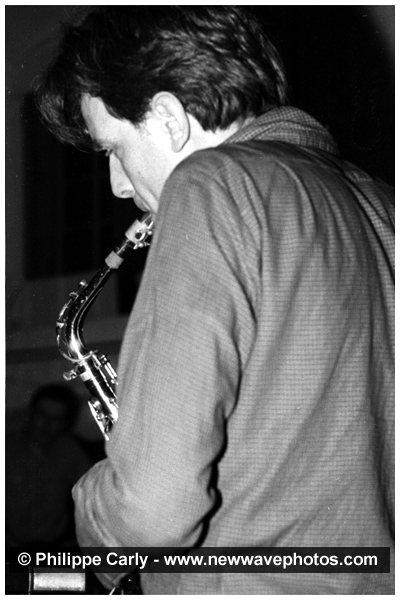

The cliché for journalists forced into writing about the album is that "the band sound like they’re playing five different songs" – and, most of the time, it is quite obvious this is bullshit. The Pop Group put the smack down on Rule of Rock ‘n’ Roll #2: ‘The band is one unit, all playing one song’, but in no way do they sound disunited. On opener ‘Thief Of Fire’ (discounting non-LP single ‘She Is Beyond Good And Evil’, stuck mysteriously at the beginning), the band’s separate elements – Mark Stewart’s animal shrieks, the funk rhythm section, Gareth Sager’s non-linear chicken-scratch guitar – play in the proper muso fashion, except for being very slightly out of alignment, a consequence of the band’s extremely primitive musical abilities and the reason for subsequent and annoying journalistic comparisons to Captain Beefheart (Mark Stewart has said "I couldn’t stand Captain Beefheart. We thought we were like Bootsy Collins or something.") The song’s gradual slide out of any semblance of ‘time’ into a nightmare of sax blurts, tape noise, rhythm and Stewart’s voice seems closer to a strategy than an accident: by refusing to train to a muso level before playing songs, the band avoids the 4/4 stasis macho white rock rhythm and aligns with the avant-garde tradition of stripping away musical clichés that began with the development of atonal music. The music sounds, more than any work of that time, unsure: at times, such as on ‘We Are Time’ it sounds like the music might shake itself apart with the fragile intensity of the playing; bass or guitar drops out, instruments stretch out, swoop in volume, speed up on tapes, fragments coming at you from all directions in some cavernous dub nightmare; Stewart’s utterly untrained voice drips with dread even as it shrieks and hollers, being swamped and silenced in feedback at the end of ‘We…’. And after all, to achieve that kind of effect takes far more effort and imagination than playing in time. What’s more, the album follows the principle of discontinuity even further, seeming to take in Burroughs’/Gysin’s cut-up principle in its collage of influences (dub, funk, Cage-ian avant-classical, punk, free jazz), the editing employed by Dennis Bovell and the band (requiring hours of tape splicing, reconfiguring the linear, twisting time to create a cubist soundspace like Burroughs’ own tape experiments) and seemingly semi-anticipating the musical collisions of hip-hop (notice the breakbeats in ‘Blood Money’; hip-hop was to be a major influence on Stewart’s experiments with Adrian Sherwood at On-U Sound).

Of course, the album isn’t all to be praised. The piano tinkling and singalong humming on ‘Snowgirl’ calls attention to the rather piss-poor lyrics (and yeah, I know the connection to Cecil Taylor and John Cage, and they’re very worthy, but it won’t save them); ‘The Savage Sea’, whilst a very pleasant piece, doesn’t really play to their strength (and the lyrics, when you can hear them… ow), and is over too quickly. ‘Don’t Call Me Pain’ starts off promisingly, then slows to a bizarrely sluggish pace , never really taking off again (and I swear that sax riff is lifted from ‘Hey, Big Spender’). But these things are partially to be expected: this is the throbbing heart of the original Pop Group project, an attempt to put the wildest collisions of theories and energies into practice, a grand experiment in sound; a musical leap into the void, the sound is sundered by the same energies that glued it together. Possessed of no musical ability, the band set out with more musical ambition and imaginative power in Gareth Sager’s thumb than in Yes and ELP’s entire careers. Combined. By an odd combination of accident and design, the band had clawed the idea of the ‘musician’ back to its barest, most nascent form – a reflection of the band’s celebration of primitivism, manifested on ‘Words Disobey Me’. (Incidentally, if anyone has any info on the Mud People of Papua New Guinea, featured on the sleeve, I’d be grateful – I can’t seem to find anything on them.) I feel loath to suggest a kinship with outsider music, but the band seems to invite it: "Culture is work and duty in the West, and anything natural is a crime", Gareth Sager told the NME. A better idea would be look at these ideas as anti-imperialist strategy taken to its logical conclusion: not merely siding with the victims of colonialism, but deconditioning, the destruction of Western culture’s grip on the psyche of the band themselves. It’s a sign of necrotic stupidity to assume that black music forms are connected to the African utopia (see the concept of jazz and blues as "primitive" music in the 1920s) the band talked about, but it’s hard not to note the addition Vaneigem gives to the above quote from Dauer: "The instant of creative spontaneity is the minutest possible manifestation of the reversal of perspective"; ‘discontinuity’ as the Northwest passage out of the bored fortress of capitalist music, into "the new innocence". By a year later, the band were encouraging people to ‘Rob A Bank’. Go figure.

These days Mark Stewart is making techno as Claro Intellecto, prepping a new album (apparently), and, no doubt, encouraging along the Bristol dubstep scene. He’s still involved in anti-capitalist activities, but I can’t help but think that he looks wistfully back on this as his greatest contribution to the cause.

1 Comments:

nice blog

Post a Comment

<< Home