The Mission Is Terminated

"When a more complex society finally becomes conscious of time, it tries to negate it – it views time not as something that passes, but as something that returns. This static type of society organises time in cyclical manner, in accordance with its own direct experience of nature."

--Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle.

There’s this band, see. Name of Crystal Castles, from Montreal, singer Alice and electronics/bass man Ethin. Their name comes from the abode of She-Ra, the twin sister of muscled alien-killer He-Man, a sculpted, long-haired example of stereotypical white man’s totty. Crystal Castles’ music isn’t in the least bit pretty: the Aphex Twin programmed on an Atari, Space Invaders come to life and bombing cities, electronic pop reduced to blank female voice and blanker thud-and-bleep. And they aren’t the only ones appropriating elements of sound and culture from the Eighties. Among those currently in their mid-twenties – those currently in the ‘vanguard’ of cultural production – there is an eighties revival going on. It can be seen in fashion, music – particularly the resurgence in electro-pop/disco, and chiptunes/8-bit music – and the Internet culture; the same images appear again and again – the Pac-Man ghosts, the awful TV of the era (The A-Team, Knight Rider, Miami Vice), the sounds of video games, Brat Pack films. Given that most of those in the supposed vanguard are children of the Eighties, one can suppose that this is merely nostalgia for lost youth.

After all, young people are more confused and vulnerable than ever before. Trapped in a system of valueless work (I know from experience that most office work is distinguished by its apparent futility and total lack of usefulness) and ‘relaxation’ that consists of hedonism, coupled with the collapse of religion, its unsurprising that they would stick to the calming totems of youth. But this is not how they’re used or seen. The defining quality of the imagery of Crystal Castles – or indeed, Gay Against You, or any of the Load Records bands, much of the noise underground – is absurdity, a sarcastic disgust for the iconography they appropriate, and for most other things. Just spend five minutes on MySpace, for Christ’s sake, and it’s obvious. Yes, it’s a ‘punk’ stance. And like punk, it’s negationist to say the least; even nihilistic. In the spirit of Dada, imagery is chewed up and spat back in the face of, well, everyone watching. In the case of Crystal Castles, the form of pop is reduced to an aesthetically scary blankness, a signifier "signifying nothing", turning music in which the pleasure principle is treasured to the exclusion of all other concerns against itself.

The tidal wave of nihilism that Nietzsche promised at the turn of 20th century is, perhaps, finally catching up with us. Whilst it has seemed to be sweeping behind us and has, in certain places and times, won out (Germany 1929-1949, the international Marxist terrorist movement, including Baader-Meinhof and the Sionese Liberation Army in the 1960s, New York and London in the late 1970s), the apocalypse he foresaw, in which, humanity would tear itself apart in apoplexy and disgust, it was avoided partly by the continued presence of retrograde moralism (that they refer to as ‘common values’) and partly by the efforts of his philosophical heirs (Camus, Simone Weil, the Situationists). But, leaving the twentieth century, we find a passive nihilism everywhere: a resigned acceptance of the illusion-world of capital, a dejected delight in the absurd, a sense in which nothing can be taken seriously whatsoever. To this generation, sarcasm and irony are air and water.

The condition known as ‘postmodernity’ has, of course, had vast amounts of ink spilled on it. However, the academic conception of postmodernism – as exemplified by Derrida, Lyotard or Baudrillard – in which the emphasis is on questioning the assumptions of philosophy and/or perception, is different from the postmodern condition that has manifested itself in our generation. It is not so much a questioning attitude, as a dejected apathy at ever finding answers, a disgust and scorn at meaning.

Most dogmatists, and those promoting traditional morality, blame this change on academic postmodernism itself, citing the backlash against it that has prevailed in Islamic fundamentalist states. The idea that people should question the assumptions of traditional dogmatic ideas angers these people, and they declare that ‘continual questioning leaves you without any answers, and no wonder these people are unhappy’. I think that rather than giving credence to the ridiculous idea that this is the fault of a handful of radical academics (who most of the general public have not read, BTW), we must examine the nature of our generation’s lives.

In the post-war years, capital in the West expanded until, by the 1960s, it had colonised every part of the individuals’ life as a source of potential commodity. Leisure time, sexual desire, even emotion and the individuals’ inner life, had been invaded and co-opted by capital. The explosion, first of the sixties counterculture (finding its ultimate expression in Baader-Meinhof), and then punk, encouraged some individuals to seek a value for life outside of the value capital ascribed to it. But this was short-lived, and whilst some individuals have sought a life that is not mere survival, capital’s growth went on regardless. With the 1980s and, in particular, the growth of the entertainment and computer industries, capital in the west grew to the point of total saturation. With the growth of the Internet, the increasing distribution of television and capital’s increasing colonisation not just of public space (think, how many billboards, how many office blocks, have you seen today?) but private space (do you own a mobile phone, a car, a house, a CD or MP3 player?), has lead to an information overload for our generation. Our continual exposure to the millions of images and words distributed throughout our lives has lead us to a mortal weariness. We hurl abuse at TVs whenever another advert for ‘no win no fee’ lawsuits comes up with their so obviously fake ‘real customers’; we watch children’s programs and daytime TV, sneering at their sheer fakeness; we find the figure of the poptimist, defending sugar-coated fakeness with a shrug of ‘it’s just fun’ such an analogue to our jaded selves.

It was Nietzsche who, at the time when the pursuit of science was driven by the tenet of ‘knowledge for knowledge’s sake’, rejected the idea that knowledge is always good for us. Knowledge that threatens life is no knowledge at all, and the wave of nihilism that had begun to infect the intellectual classes in the 19th century was brought on by too much knowledge, an abundance that cause "spiritual indigestion". At some point, the mind gives up choking down facts – and, now, images, messages, lies – and regurgitates them. This is exactly what is happening, as we approach the fourth decade of the information age.

***

The return of the Eighties is not in form only, but in content. The content of the popular arts – television, pop music, multiplex film – is returning to the laughably bad, astonishingly expensive level of the 1980s. The resurgence of ‘luxury goods’ to match bourgeois and petit-bourgeois ambition – organic food, ‘minimalist’ furniture such as The Cotswold Company or Bo Concept, designer clothes now flooding the high street – has been matched by a resurgence in yuppieism that is infecting this entire generation. The main ambition of most of my friends is to "earn more than 30k a year"; even in the tiny insurance firm I work at, the brokers swagger and boast like testosterone-pumped chimps, dress in unnecessary suits and aspire to driving Beamers. Nothing more. Very few people I know read, or take part in art, or see music as anything other than aural wallpaper. Most of them couldn’t give two shits for the dispossessed, or those mulched by capital; they usually assert that the lower classes "deserve to be there", and that the logic of the market – all against all – is "the way the world is". When they speak, it’s the voice of Gramsci’s Hegemony, all slick syllables and bared fangs.

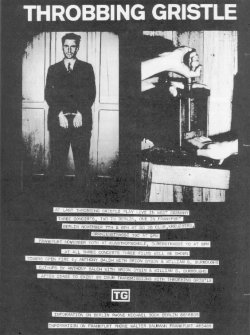

At the same time, Throbbing Gristle have just returned with their first album since their split in 1981. Though they emerged from the hippie underground in the mid-70s, TG were a shamanic conduit for the psychic turmoil of the late 1970s. The insidious terror and bludgeoning weight of their last three records – The Third Annual Report, 20 Jazz Funk Greats and 1980’s Heathen Earth – as well as the singles ‘Subhuman’ and ‘Discipline’ were a suitable preface to the long nightmare of the 1980s; a soundtrack to apocalypse.

TG’s sudden reformation in 2004 and their decision to make an album as queasy and toxic as The Endless Not is pretty damn worrying to those of us who know our history. If the world has reached the point again where we need Throbbing Gristle’s crisis-noise, we’re in for a rough ride. The continual panic-mode of this government certainly does not give us cause for ease: not only this government’s continued destruction of the public sector, but its paranoid rhetoric about "the enemy within" recalls the Thatcher government’s siege mentality; its campaigns against the anarchist movement, the nuclear disarmament movement, the trade unions, the miners, the legitimate sections of the Northern Irish Republican movement, were all accompanied by the same stigmatisation that characterises the target as the dangerous Other, as is used against sections of the Muslim population today.

But it goes even further than this. There is now a regime in the White House that perfectly mirrors the Reagan administration, even down to its foreign policy, even targeting the same enemies (Iran) once again. This is matched by a British government whose foreign policy outstrips even Thatcher – our adventurism in the Balkans, Afghanistan and Iraq has committed far more men and killed far more than even the Falklands offensive ever did. Both Blair and Bush have acknowledged their admiration for Thatcher and Reagan respectively, and actively are pursuing to resurrect an Atlanticist foreign policy based around ‘enlightened’ interventionism.

The past can never return completely, only in transmuted form. What were once real become ghosts, oracles of powerlessness, stranded in the present. The increasing tendency of contemporary art to look back, not only to the Modernist period, but to the conflicts of the past (such as Jeremy Dellar’s reconstruction of the Battle of Orgreave), as well as the recent growth of ‘hauntology’ is the most telling symptom. This is most obvious in the ‘AIDS Uncanny’ series by sound-artists Ultra-Red (written about here by k-punk). The subtitle, ‘time for the dead to have a word with the living’, perfectly illustrates the nature of the return the Eighties has made: the epidemic, which neither Reagan nor Thatcher attempted to stem, continues unabated, and the conflicts of AIDS activists to bring it to public attention, to bring about a solution, haunt the pieces, as options closed down, as blind alleys, as the voices of the dead interpreted through the medium of electronics. The post-punk revival of recent years also posits a strange return: the resurrection of a musical style suggests a resurrection of the circumstances that brought it about. But no such thing occurred: if post-punk was created in an atmosphere of political turmoil, material poverty, and a record industry bulldozed by the contained anarchy and radical demands of punk, our generation is the most materially spoilt ever, with a political system in which all parties occupy the middle ground, and a record industry more bumbling and monolithic than any time since the mid-70s. In particular, the post-punk period was characterised by a Year Zero attitude that took pre-punk music as material for its own radical explorations, whereas the post-punk revival is based on the fetishisation of that period’s music. In particular, Joy Division and Ian Curtis, whose legacy has been combed over continually in an almost necrophilic fashion. Curtis’ image, replicated continually, and his biography, dogged by the hindsight of his death, have been used and re-used: his absence has become a presence, a ghost clad in early-80s austerity, haunting the airwaves; the re-broadcasting of his image has given him a kind of eerie second life, but the image itself is completely intertwined with death, just as it seemed to exist in the psychogeography of the ghost towns of early-80s Britain.

In this sense, what we are witnessing is not necessarily so much a periodic shift in cultural perception back to mentality of the ‘80s (such as the shift that occurred in the 1980s back to the Cold War logic of the 1950s), but the creation of a copy of the ‘80s, a bleached-out, exhausted memory.

***

For Fukuyama, 1989 marked ‘the end of history’, the point at which the neo-liberal capitalism defeated corrupt socialism, creating a worldwide paradise, in which capitalism would expand to satisfy man’s primeval desire for permanent ease. It was to be the end of strife, the point at which Marx’s historical dialectic would reach equilibrium. He was perhaps right about one thing: what 1989 marked was the death of forward motion for history. From the beginning, the 20th century, and the idea of modernity, was bound up with speed, progress, continual forward motion. All the utopian projects of the early 20th century – in particular, the Modernist project in culture, and the Soviet dream conceived in 1917 – were geared around this. By 1989, the Modernist impulse had guttered out, exhausted by its own relentless pace and the existential horrors of Auschwitz and Hiroshima; the collapse of the Soviet project marked, for many, the end of the hope for any system outside of capitalism. It was the end of the idea that people could be subjects rather than objects of history.

People may claim that the death of socialism was not the death of history; they point to globalisation as evidence of the rapacious capacity of capitalism to create the new. But the capitalist system, dedicated to the reduction of life to the economic means of survival, was, by its very nature, a system static in terms of ideas; the Thatcher and Reagan administrations were dedicated to the resurrection of retrograde moral values that would maintain the imposed social hierarchy, the status quo. Capitalism may have embraced technological change, but it forbade it from causing any social change. With 1989, we entered a strange afterlife, a post-history. The 1990s brought, in the form of Clinton and New Labour, a supposed new dawn after the darkness of the Cold War, the victory of optimism and humanitarianism. But these have turned out to be nothing more than red herrings; both have resorted to the tactics of Thatcher and Reagan.

The idea that humanity can progress any further has now become laughable to most people. For those emerging out of the Eighties, now the generation entering its twenties, there was no future; it had been exhausted. We can see, by the early 1990s, that the whole psychic atmosphere of the West was one of discontented, wearied resignation: as Elizabeth Wurtzel pointed out in the Epilogue of Prozac Nation, rates of mental illness, depression and suicide grew enormously in the early 1990s. The continual, exhaustive battering of our generation by the system of capital, its continual, oppressive presence and the sensory-information-overload that it has delivered into our lives, has made the past the only thing we have. The record is skipping; history has contorted into a Moebius loop. The smug, supposed victory of western capital has not even come into being: history is replaying itself just as Western politicians want, but with new ghosts haunting the song; the dangerous Other of fundamentalist Islam, birthed, you may remember, with the 1979 Revolution in Iran, then nurtured by the CIA in Afghanistan. Where we will go from here is anyone’s guess, but the one thing everyone agrees is that it’s going to be rough.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home